The European Commission has selected 13 strategic mining projects in non-EU countries to strengthen Europe’s access to critical raw materials. The initiatives, selected for their strong environmental, social, and governance (ESG) credentials, aim to bolster the EU’s access to critical raw materials that are vital for the green and digital transitions. The projects will increase economic resilience in key sectors like electric vehicles, renewable energy, defense, and aerospace.

The EU’s focus on strategic mining abroad is driven by geopolitical and industrial urgency. Access to materials like lithium, cobalt, rare earth elements, and copper is essential for electric vehicles, wind turbines, solar panels, and digital infrastructure. Europe currently relies heavily on a handful of countries for these resources. For instance, China for rare earths, the Democratic Republic of Congo for cobalt, and Chile for lithium. These dependencies carry both political and environmental risks.

The newly selected projects are in partner countries such as Canada, Zambia, Ukraine, Brazil, and the UK. Together with 47 previously selected projects within the EU, they mark a milestone under the Critical Raw Materials Act, in force since May 2024.

By supporting new ESG-vetted projects abroad, the EU aims to de-risk supply chains while promoting sustainable development in emerging economies. But the strategy also involves significant environmental and social trade-offs: new mines, however responsible, still disturb ecosystems, consume large quantities of water and energy, and often generate significant carbon emissions.

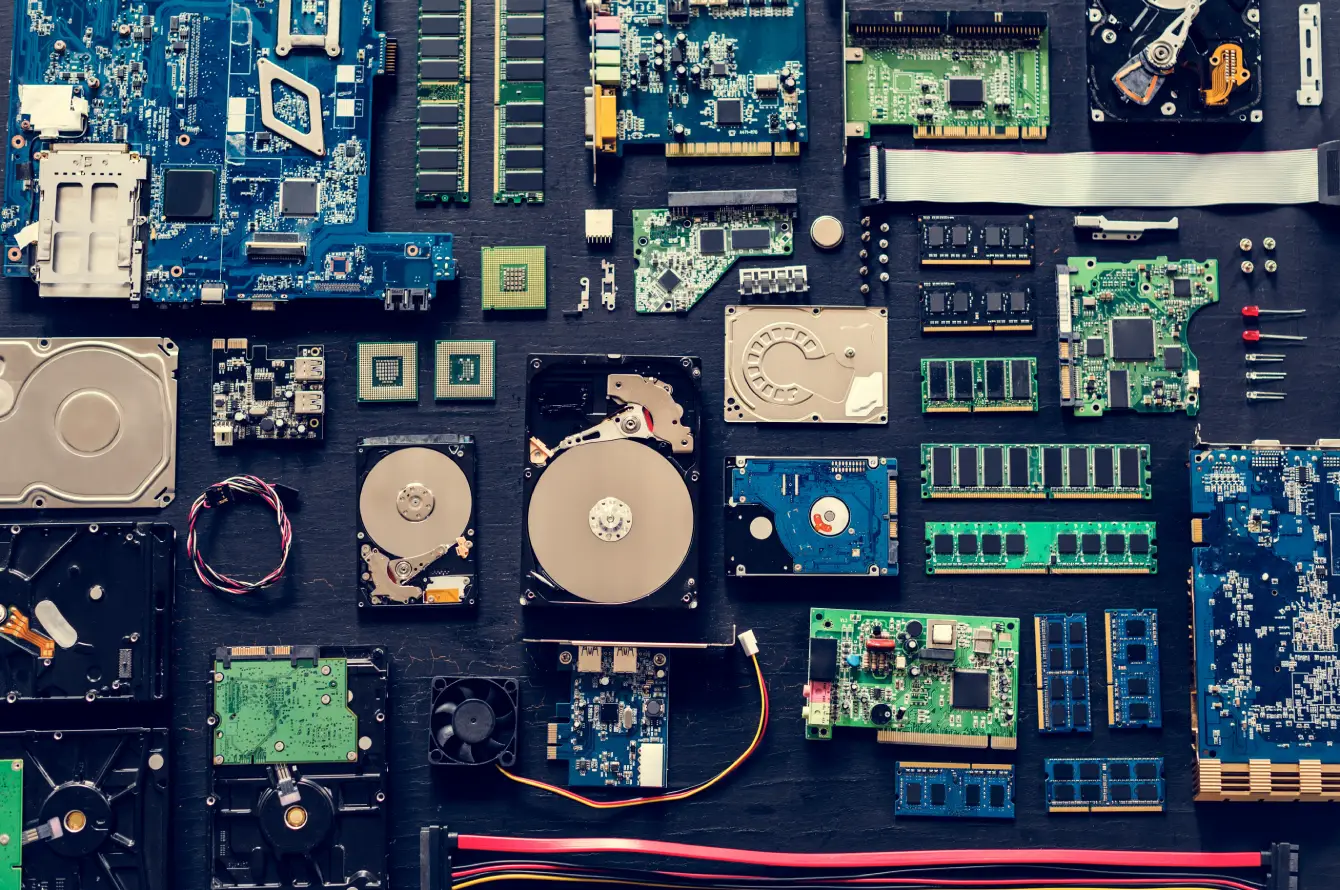

Urban mining

A circular alternative to get these materials is through urban mining. Urban mining refers to the process of recovering valuable materials from waste like used electronics, buildings, and infrastructure. Basically, it is tapping into the ‘above-ground mines’ we already have. Europe generates millions of tonnes of electronic waste, or e-waste, annually. Much e-waste contains high concentrations of critical raw materials.

For example the vast majority of us own a smartphone. Inside each smartphone are metals and minerals that could help the environment. Since one iphone holds up to 0,034 gr of gold so one tonne of discarded smartphones contains up to 300 grams of gold. In Japan, materials recycled from old electronics were used to make all the medals for the Tokyo 2020 Olympic Games. In Sweden, a company called Stena Recycling runs one of Europe’s most advanced e-waste facilities, recovering copper, aluminum, rare earths, and plastics from used electronics.

Urban mining reduces the need for new extraction, minimizes environmental degradation, and contributes to a circular economy. It also tends to generate local jobs and reduce geopolitical risks, since the raw materials are sourced domestically or within the EU.

But despite its promise, urban mining is still rare practice due to practical barriers. The low collection rates for instance are not helpful to urban mining. In the EU less than 40% of e-waste is properly recycled.. Furthermore extracting rare materials from complex devices is still costly and technologically intensive. And finally, there are policy gaps. While the EU promotes circular economy principles, financial and regulatory incentives for urban mining are still relatively weak compared to primary extraction.

€5.5 billion

The EU’s new strategic raw materials projects are expected to mobilize €5.5 billion in investments. With an estimated value of €25 per kg (average across lithium, cobalt, copper, rare earths), that represents 220 thousand tonnes of critical raw materials. To get the same amount from urban mining, it is necessary to process 2.2 million tonnes of e-waste. The EU generates over 11 million tonnes of e-waste per year, collecting 40% of it. So Europe could potentially recover the same volume of materials without digging a single new mine.

The EU’s €5.5 billion bet on international mining projects sends a clear signal about the importance of raw materials for Europe’s future. It is crucial in the short term. But for a truly sustainable and resilient raw materials strategy, Europe must scale up urban mining. It is necessary to improve e-waste collection and recycling. Resource recovery must be embedded into product design, procurement, and waste management systems. If Europe is serious about sustainability and sovereignty, tapping into our own urban ‘mines’ may be not just a complement, but a necessity. Urban mining must move from the margins to the mainstream.